Another year is done. A new decade begins and, in the work of a second, one year hands its heft and weight to the next. At the stroke of midnight, my family strip off our socks, put on our most outrageous coats, and together we run around our house. As our bare feet scrape against the snow, shouts and swearing and the pain of our cold toes give meaning to the first few seconds of this new year.

These first seconds accumulate into minutes and hours and days until the next year shows its face, reminding me that we are constantly building on the past, on time, on dirt, on history. With words and science, art and mythologies, we are constantly trying to make sense of what we’ve built, of the cycles of the world around us.

Many ancient mythologies attempted to explain fundamental parts of the world through stories. Over the years, these origin stories have evolved into science. Our human craving to explain things much larger than us, very much out of our control, has led us to labs and data and theses. But before we knew that the seasons are caused by the axis of our planet, stories like the Greek myth of Demeter (Goddess of the Harvest) and her daughter Persephone (Goddess of Springtime and the Underworld) told of how the seasons were created by women’s grief.

In classicist Edith Hamilton’s rendition of the Homeric Hymn to Demeter, Persephone (daughter) is kidnapped and raped—with Zeus’ (father) approval—by Hades (uncle) and taken to the underworld (death). Above ground (life), Demeter (mother) mourns daughter’s fate, and the harvest stops, people starve “Nothing grew; no seed sprang up”. Father sees his mistake, sending a messenger to bring daughter back from the dead. But as daughter leaves death, uncle forces her to eat a single pomegranate seed, for if daughter eats food of the underworld she is sentenced to “return to him.”

Over and over, springtime arrives as mother celebrates daughter’s return to life, winter follows as mother mourns daughter’s return to death. Out of this cycle of women’s grief, the seasons are born. Out of the seasons, a myth takes shape. Out of mythologies, eventually, our scientific understanding of the world emerges.

Out of the seasons and seconds and days and years, our lives take shape and find their paths. As a new year dawns, as the snow sticks to the barren ground, forward motion means looking, first, at the past. A past I’ve learned is constantly maintained and challenged by how we tell and retell it. I remember walking through the galleries at the Detroit Institute of Arts, pale faces in the classical paintings loomed down, telling stories of power, darkening the rooms. Turning a corner, I found Kehinde Wiley’s Officer of the Hussars and could feel the weight of history staring back at me. In those brushstrokes, Théodore Géricault’s 1812 work and history and mythologies crash into the present, leaving complicated truth roiling within the subject’s eyes and dark, unflinching face.

This challenging of the past through the present lens is present in all of Wiley’s work–whether it be Napoleon Leading the Army over the Alps, the presidential portrait of President Barack Obama, Three Girls in a Wood, or countless other paintings. Each laborious work holds history’s mirror up to the present that resides within the eyes of each subject, inviting us to take a closer look. As Wiley said in an interview about his St. Louis exhibition,

“The great heroic, often white, male hero dominates the picture plane and becomes larger than life, historic and significant […]That great historic storytelling of myth-making or propaganda is something we inherit as artists. I wanted to be able to weaponize and translate it into a means of celebrating female presence.”

In art and myth and science alike, history’s perspectives remind us that without the past, we humans wouldn’t be equipped to reinvent the future. This reinvention begins with education. Looking into the word’s past, educate comes from the Latin “educere” meaning “to lead out”. Within higher education, the challenge is to bring education back to its conceptual roots, as education innovator Cathy N. Davidson writes in The New Education:

“Whereas the research university puts its institutional reputation first, community college prioritizes student growth. Rather than beginning from a fixed standard of what counts as expertise […] community college takes any student at any level in order to help that student reach their goal.”

Community college has the ability to recreate the atmosphere of education, making knowledge and growth more accessible. Using the example of a community college’s innovative programming, in quoting John Mogulescu, Davidson explores how education can use the past to its advantage by “trying new ideas, comparing the new with the old, building on what worked.”

In the face of this new year, this new decade—in the 20s, I will pursue my higher education, challenging the old, interrogating the new, and “build on what worked”—every second is a time to run barefoot through the snow and eat pomegranate seeds. Every second is a time to question and imagine, to “lead out” what is folded within history so that we might work toward futures built from our own stories.

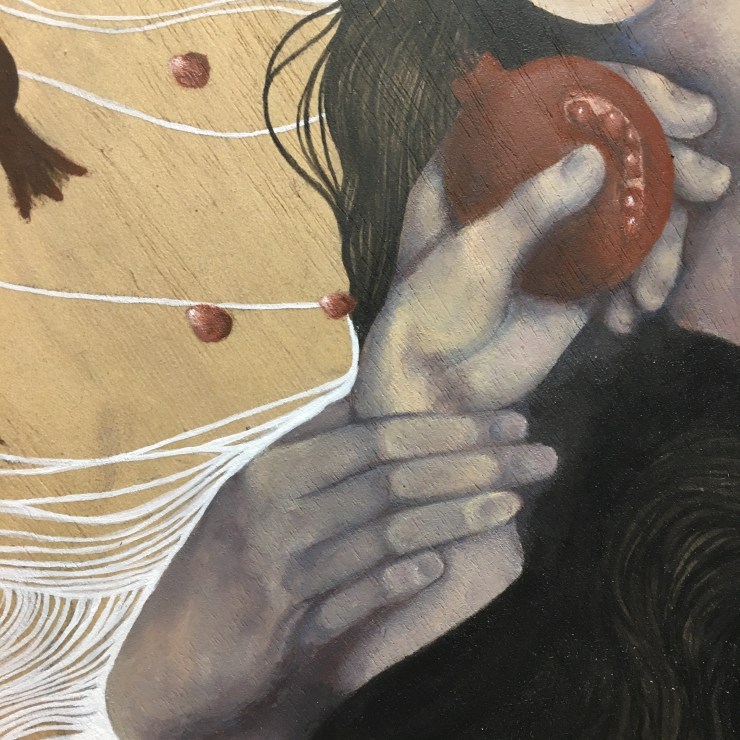

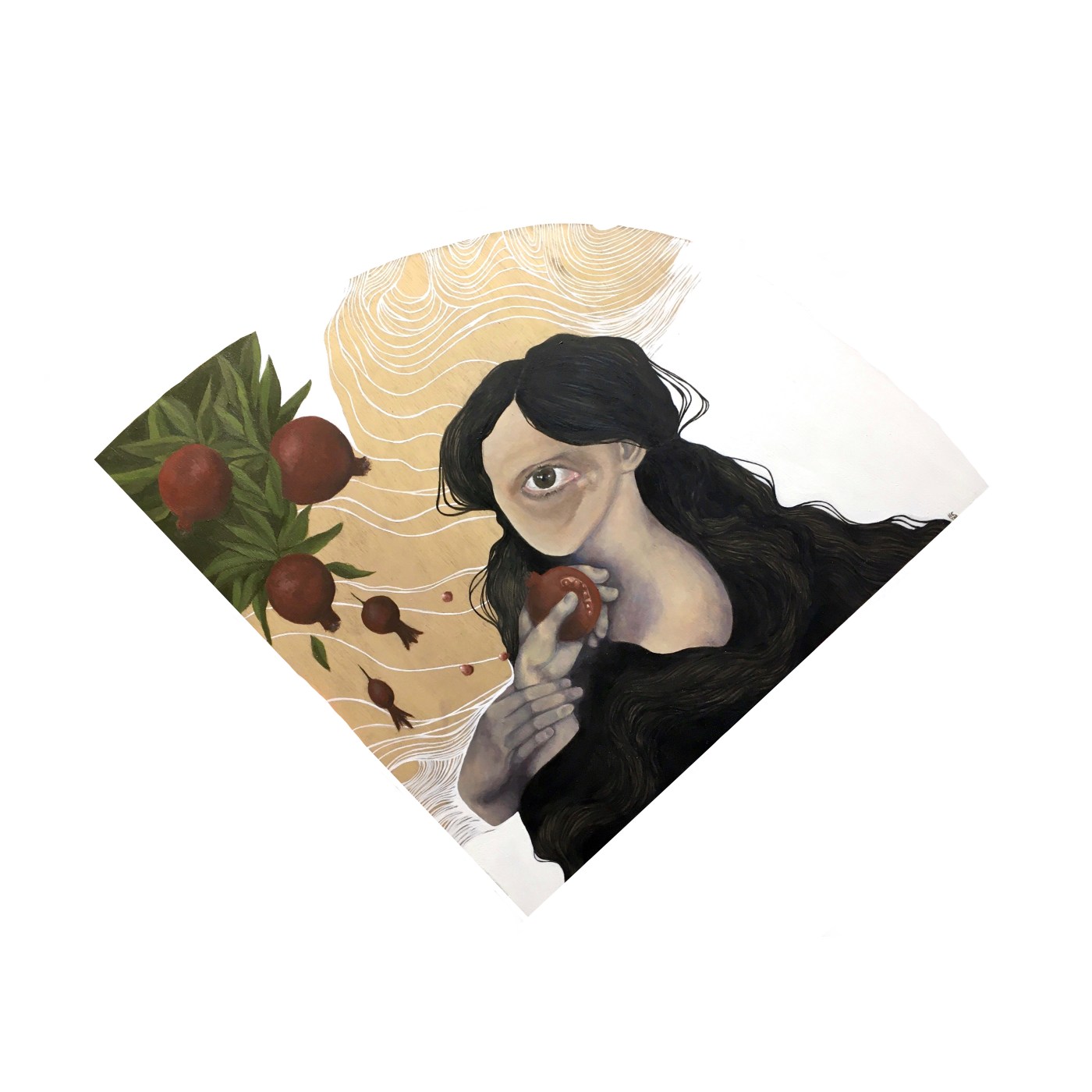

Painting inspired by the myth of Persephone, my mother’s grief, and Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s Proserpine: