Matteo Farinella: The Curiosity of Communication: Inspired by the Artistic Work of Santiago Ramón y Cajal

Ink on paper

“‘Curiouser and curiouser!’ cried Alice”

Lewis Carroll, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland

Curiosity leads me through life, pulling me down rabbit hole after rabbit hole. Questioning has the power to open up doors which can, in turn, open up the world. So, with curiosity at your side, let me lead you down a rabbit hole, one full of more rabbit holes and facts and neurons. Hang on, have patience, and let the rabbit hole lead you where it may.

Second only to my love of art is my love of story, and second only to story is my love of science. This love of science comes from the minds of those specks on a blue dot floating in the universe who ask questions and communicate the answers they find. When I was in my early teens, my fascination with neurons began. The inner workings of my brain and mind were a mystery I wanted to explore much more than I wanted to solve.

My interest in neuroscience led me first to David Macaulay’s book The Way We Work. His illustrations of neurons and synapses and dendrites and somas kept me company until last fall when my sister and I came across HarvardX’s course “Fundamentals of Neuroscience.” Being the curious teenagers we are, we jumped headfirst into the first rabbit hole of this story: we researched the teachers.

First, we found Nadja Oertelt, a co-founder of Massive Science, a project and website about sharing scientific stories and information “in pursuit of a more informed, rational, and curious society.” Moving on from Massive, we turned to Nadja’s Twitter page. She had just posted about her Kickstarter “Women of Science Tarot Deck.” My sister and I witnessed the worlds of art and science and feminism come together, and we were inspired.

Nadja Oertelt created the “Women of Science Tarot Deck” with fellow science communicator Matteo Farinella. Matteo’s work, as an illustrator who received his Ph.D. in neuroscience–apart from being incredibly cool and the sort of work I dream of doing one day–is very much about communicating. Now for the second rabbit hole: we learned that science communication is, as the Wikipedia page writes, “the practice of informing, educating, sharing wonderment, and raising awareness of science-related topics”.

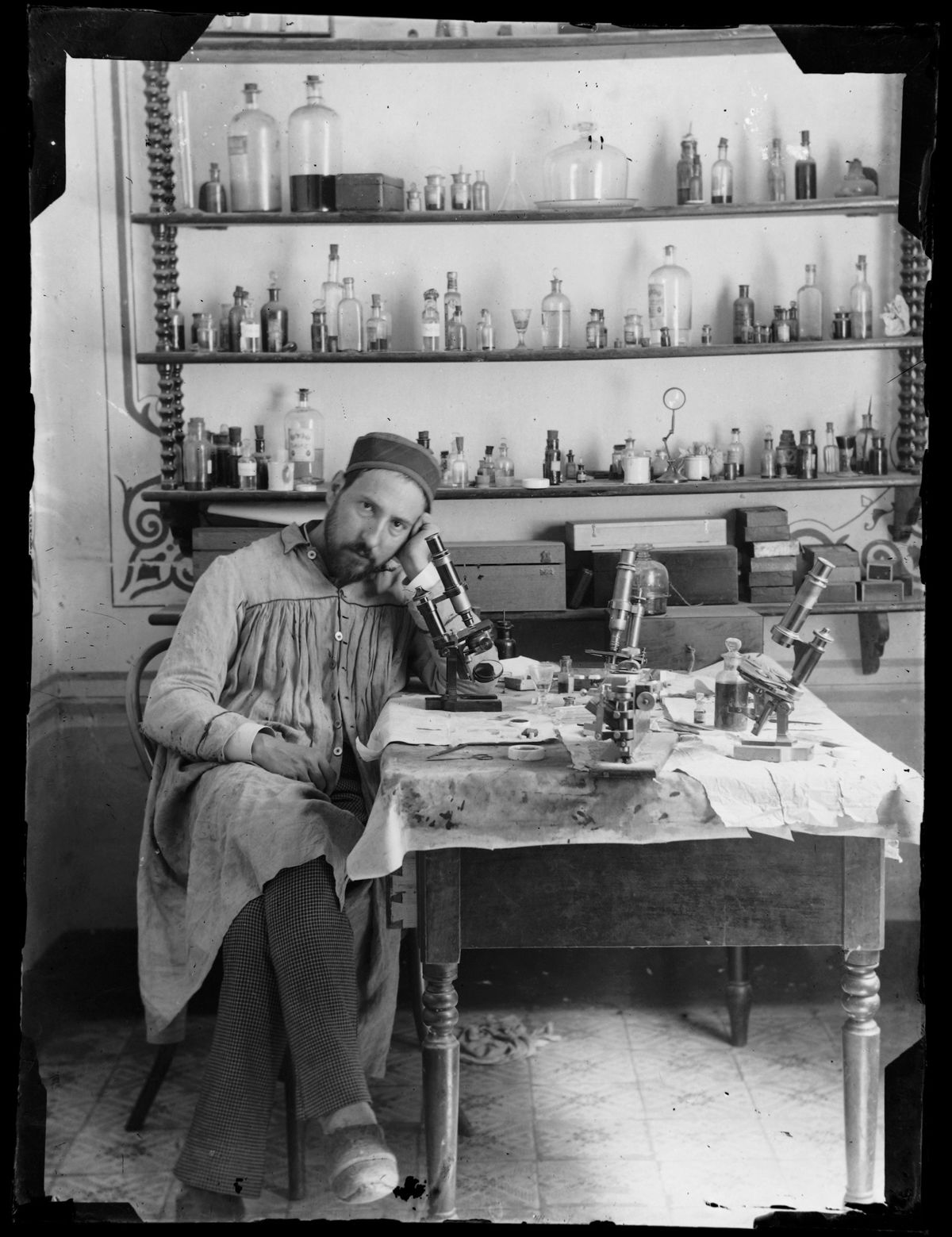

Along the same lines, Matteo’s project “Cartoon Science” is facilitated and inspired by his work studying “visual narratives in science communication” at Columbia University. On the website, Matteo writes that “scientific research should be open and accessible and I think visual narratives can play an important role in bridging the gap between academia and the general public.”Matteo and Nadja’s work filled us with questions and inspired us to communicate. Then the third rabbit hole came our way when we asked Nadja and Matteo for an interview with our nonprofit Look Wonder Discover. One question led to another, and I asked Matteo if I could draw his portrait for CognEYEzant:365. He shared his favorite artist along with the explanation that Santiago Ramón y Cajal was “a bit of a trick.” Matteo shook loose a memory: years earlier, I had read Barbara Oakley’s book A Mind for Numbers and had been captivated by a photograph of a man staring intensely at me, that man was Cajal.

Santiago Ramón y Cajal has been considered “the father of Neuroscience,” but his Nobel prize-winning discoveries may not have been possible without his ability to draw. He didn’t just show his work, he communicated it, his drawings illustrating the relationships between the neurons beneath his microscope. Cajal drew because, as Oakley writes in A Mind for Numbers,

“he never felt that photographs could capture the true essence of what he was seeing”.

When I poured through Cajal’s drawings, when I read Matteo and Dr. Hanna Roš’s book Neurocomic, I began to understand that neurons are the building blocks of how we understand and communicate with the world. As a page in Neurocomic reads:

“It all begins and ends with neurons: from your sensory receptors to the nerves that control your muscles. Everything you feel, remember or dream, is written in these cells.”

Matteo’s art communicated scientific theory, process, and history in a narrative form reminiscent of a certain girl falling down a certain rabbit hole. Matteo’s art, through story, engaged me and reminded me that I am a piece of science, a collection of neurons on a blue dot floating in the universe. Reminded me that I had just stepped into the world of neuroscience equipped with curiosity, just opened one of many doors, jumped down one of the many rabbit holes.

As Neurocomic ends, the protagonists acknowledge the existence of the reader, and that connection between reader and story made me wonder if the connection between art and science, and us, is communication. Similarly, Matteo and Cajal’s work makes me wonder if science is a language we can use to understand and communicate with the universe and if art, in turn, is a language we can use to communicate with ourselves and with each other.

And perhaps, when art and science come together, they communicate a language that imprints itself inside you so that long after you’ve seen Cajal’s drawings, you can still imagine his illustrated neurons twisting and firing within you.

357 days done, 8 to go.