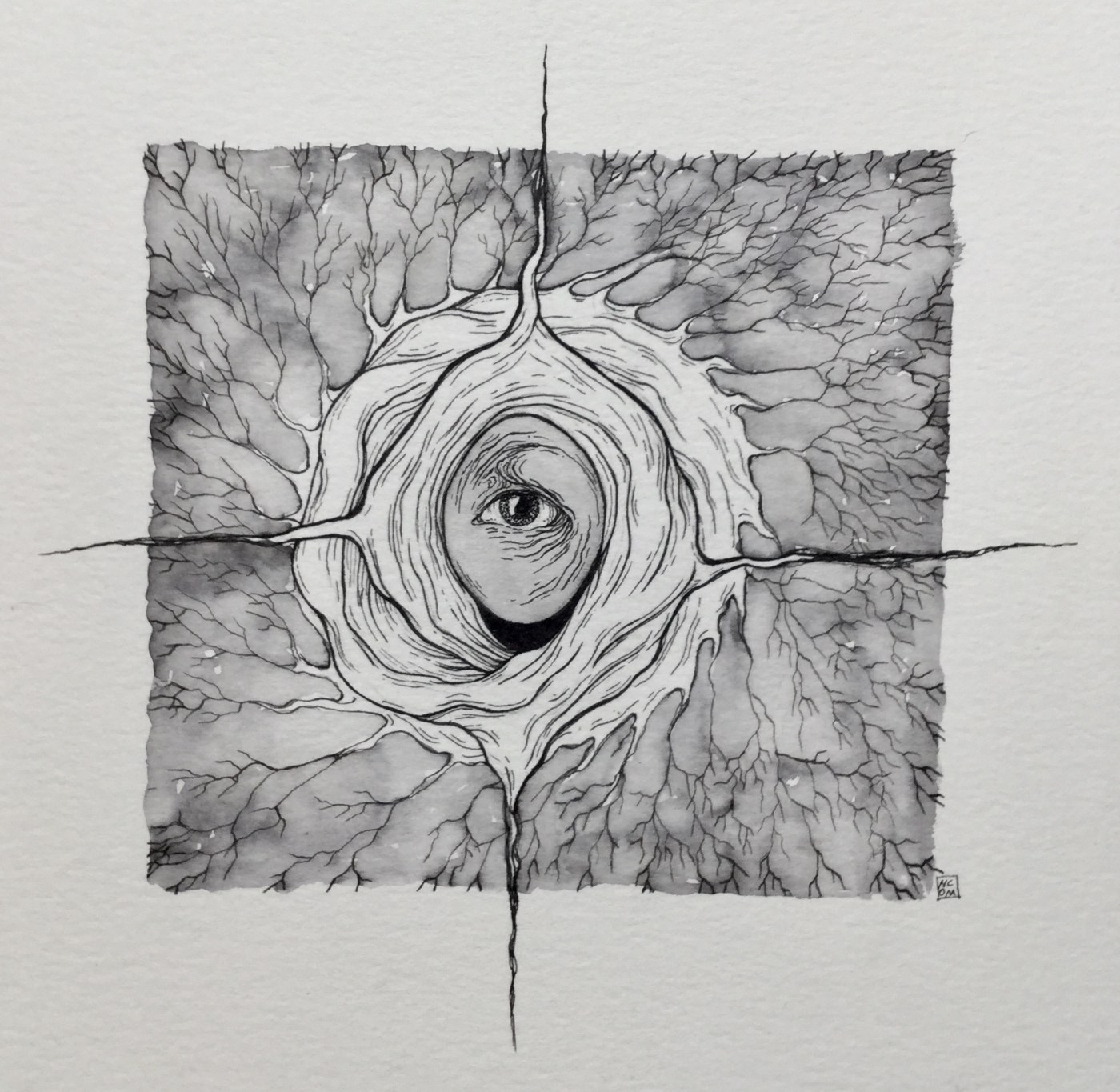

Childhood, Connection, and a Collection of Sevens: Inspired by Jamie Sams and Native American Medicine

India ink on paper

My childhood isn’t over. Some say that childhood ends when you turn 18, but as I near my 19th year, I feel closer to my childhood every day. When I was little, I knew how to be present, my small body was grounded, and in that time, I began to absorb everything I could. What I absorbed back then creates correlations and coincidences that connect my past to what I experience today. And because of this, I am not entirely sure I will ever “grow up.”

My relationship with the forest around me began tentatively, while I loved nature, I was terrified of bugs, and I didn’t particularly like the vulnerability of being outdoors. I grew up in the woods beyond the Sleeping Bear Dunes National Lakeshore. Our house is miles from the nearest gas station, in a matter of steps, my backyard turns into hundreds of thousands of acres of State Forest.

My mom grew up in the inner city and, unlike my father, was very wary of the woods. Together, she and I were very aware of the vastness behind our house, of the black bears that ransacked the bird feeders, of the mountain lions that turned from tall tales into reality. Through the big window in our kitchen, I learned to love outside through observation. I remember my little hands filling in charts recording how many feet of snow fell that day or which birds and animals visited the yard.

Over time, my observation turned into experience and reverence. Only recently did I walk alone through the crunchy leaves, listening to the sounds and peace around me. The vastness, vulnerability, and mystery that unsettled me when I was little now make me feel safe.

Perhaps this is because of the stories I absorbed as a child. My mom read Louise Erdrich‘s “The Birchbark Series” aloud to my sister and me. I imagined that I was connected to the protagonist Omakayas’ world through her eyes and story and through the forest creeping into my back yard, so similar to the woods her Ojibwe tribe would have lived in. Understanding this forest, though, was not fiction or a part of the past. Other stories glued together past and present and place. We learned about Indigenous perspectives of Thanksgiving from a family friend Ken, who passed away just last year. His photograph is in National Geographic’s book 1621 A New Look at Thanksgiving, and seeing my friend’s face in a book, in “history,” began to show me how the walks alongside us, within us.

From stories and observations, concepts like fate and spirituality twisted in on themselves. As I began to reflect on my own spirituality, right around the time I began walking alone in the forest, I felt the frustration that the religions I was familiar with seemed to limit meaning and the universe much the way illustrations of storybook characters didn’t live up to my imagination. Then, just last week, I found an “illustration” that began to do justice to my atheistic sort of spirituality: Jamie Sams’ work with Indigenous American belief.

Sams is an Indigenous American writer and artist whose Medicine Cards found their way into my teenage years, the battered and used cards have been with me nearly every day. Just last night, I began to read Dancing the Dream: The Seven Sacred Oaths of Human Transformation. And through my murky tiredness, on the first page, Sams seemed to be speaking not just to me but to my child self:

“Every human being who walks the Earth Mother has an individual sacred path through life […] created by the weaving of many tangible and intangible threads, which connect all emotions, dreams, thoughts, and experiences. The spirit’s invisible thread of life force unfurls at birth and carries us thought the twists and turns of growing up and learning about life on planet Earth. Our lives will change directions many times as experiences urge us to grow.”

On the very next page, she writes of the beginning of our lives, lives that were “exhaled from the Creator, the Great Mystery” And there it was, the Great Mystery, a name for the feelings I experienced so long ago, observing the world as it is in the present. This present is the Seventh of the Seven Sacred Paths or directions. The Paths East, South, West, and North we often think of as directions that take us from one place to another. Yet on the medicine wheel, they become: East, illumination and clarity; South, rising above human reactiveness; West, the healing of the past and our bodies; and North, sharing wisdom and open hearts. The Fifth and Sixth Paths, the Above and Below Directions, connect us to the universe above our heads and the earth and history at our feet, these directions root us in the world. While the Seventh Path, the Within or Now Direction, roots us in ourselves and in the present. The Seventh Path makes me wonder if perhaps time and history are just collections of “nows.”

Many aspects of modern, colonized culture are losing and have oppressed this kind of deep, personal, and universal presence. In Dancing the Dream, Sams writes, “Since the late 1500s, with the coming of the conquistadors, practicing the spirituality of our ancestors was punishable by death.” And later on, Michael P. Guéno’s Oxford Research Encyclopedia article “Native Americans, Law, and Religion in America” writes that, on April 10, 1883, “Native American dances, the practices of medicine men, and in effect Native American religions were legally banned with the promulgation of the ‘Rules for Indian Courts’.” Only recently did the United States government pass The American Indian Religious Freedom Act on August 11, 1978. The Act’s policy is:

“to protect and preserve for American Indians their inherent right of freedom to believe, express, and exercise the traditional religions […] including but not limited to access to sites, use and possession of sacred objects, and the freedom to worship through ceremonials and traditional rites.”

According to Sams, it was not until 1989 in Mexico that “the first intertribal Native American ceremony was allowed to be held in public.” In The U.S. in the same year, “Congress passed the National American Indian Museum and Memorial Act to begin the repatriation of Native American and Native Hawaiian artifacts procured through questionable means.”

These events barely scratch the surface of history, there are so many destroyed and repressed stories and perspectives. My understanding of Indigenous American history, spirituality, practices, and current culture is just beginning. Yet, from what little I know, I deeply believe that each story and each memory keep a culture, preserved primarily through oral tradition, alive.

While we walk the Seventh Path, in our “Now,” we must learn to remember presence. We must learn to remember the ancestors that walked and thrived on the earth we now inhabit, so our future will be shaped by all the witnesses of the past.

In Jamie Sams’ vision, “every time we allow ourselves to use our imagination, we change our view of reality.” And perhaps, to regain the art of presence, we must first imagine ourselves as children. Children living moment to moment, open and consciously receptive to the universe and to the complexity of people and nature around us. From here we can remember and move forward through the many directions that surround us.

334 days done, 31 to go.